What Bernie ‘Saw’

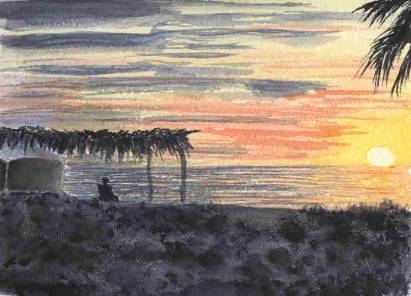

Marnie and I had been camping near a Mexican fishing village on the Pacific for a few weeks, and had settled into a most enjoyable routine of 10 km dawn hikes followed by breakfast and a leisurely coffee under the coco-palms as we watched flights of pelicans skimming the curling breakers in search of schools of young tuna and sea bass. On such a morning we saw a pod of dolphins racing through the surf, and on a special day saw a huge whale about a half mile off shore, surging partially out of the water, sounding, and smacking its huge flukes on the ocean surface. Around 9 each morning, the fishermen would be returning to their village after clearing their nets that had been set the prior evening, and soon thereafter we would stroll into town to the fishermen’s cooperative to purchase fish and visit the small tiendas for vegetables and bread. As can be seen, we led a hectic life and had such a lot of things to take care of before we could get back to our hammocks and books.

For several days I was absorbed in a book by the Oxford zoologist Richard Dawkins called “The Blind Watchmaker”, wherein he explained how through evolution there had come to be such diversity, and the specialization of senses within different species so that each could compete and ‘make a living’ in their competitive niches and habitats.

Dawkins detailed such things as:

· how eyes developed from photosensitive skin patches, via natural selection [in the darkness of the ocean, 1% vision = survival in a world of where the ‘competition’ has 0% vision].

· how, as life forms evolve to ‘make a living’ in their competitive niches, congruence of form and function is noted between unrelated, distanced species – e.g. electric fish in both Africa and South America; driver ants (Africa) and army ants (S.A); placental mammals and marsupials; termites and ants which resemble each other because of evolvement within similar habitats (although termites are related to cockroaches, ants are related to bees and wasps)

· how, in embryology, all the cells in the embryo contain exactly the same set of genes, but different cell groupings are switched on and off at different stages of zygote development to form various parts/organs/limbs of the nascent body. [Dawkins indicates that the process is neither blueprint nor epigenesis (cookbook) – science as yet doesn’t understand many things about how creatures develop from fertilized eggs].

·

Fascinating

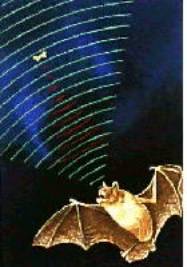

was a section describing the astounding echo-location of bats. Echolocation

works like the radar or sonar in planes and ships. Night-flying bats use high

pitched ‘clicks’ or squeaks to bounce a sound wave off its prey (fly or moth);

the bat picks up the returning echo and its brain ‘models’ the echo into a sound

picture indicating the size and shape,

direction, distance, and motion of its prey which is then honed in on

and intercepted in mid-flight. Bats, which are highly maneuverable but

relatively slow fliers compared to birds, are thus able to ‘make their living’

at night when there is less competition from birds, and less danger of being

attacked by larger birds of prey.

Fascinating

was a section describing the astounding echo-location of bats. Echolocation

works like the radar or sonar in planes and ships. Night-flying bats use high

pitched ‘clicks’ or squeaks to bounce a sound wave off its prey (fly or moth);

the bat picks up the returning echo and its brain ‘models’ the echo into a sound

picture indicating the size and shape,

direction, distance, and motion of its prey which is then honed in on

and intercepted in mid-flight. Bats, which are highly maneuverable but

relatively slow fliers compared to birds, are thus able to ‘make their living’

at night when there is less competition from birds, and less danger of being

attacked by larger birds of prey.

One morning we were surprised to look up and see a spry, diminutive older lady walking around an adjacent restaurant and through the palms toward us. She was tapping with a white cane and had a small dog on leash, and seemed to carry on a continuous soliloquy with her pet. Her progress was surprising in a way, since she walked fairly quickly over the uneven ground without running into obstacles. It was as though she was in her own world. She didn’t seem to notice our rig off to the side of her path and appeared startled when we called to her. She graciously accepted our offer of a soft drink and a seat in the shade, and with encouragement told us her story. She was a Canadian, an army vet, and had even lived in our own town of Orillia as a young adult, but for many years has summered in British Columbia. Her name was Bernie, and her little dog was called Sadie.

Bernie had been driving by herself into this part of Mexico each winter for almost 40 years until three years previously, when she lost most of her eyesight as a result of macular degeneration – a progressive, irreversible affliction which by this time had left her totally blind in one eye, and with only 5% peripheral vision in the other. Still, she loved her Mexican winters so much that she and Sadie flew down and she was able to arrange help with her luggage and with transportation and then find accommodation in the village by herself – a most resourceful lady. Although Bernie was now in her ‘80s, her mind and her memory was keen – she enquired by name of old friends in our town – friends that had been left behind 50 years before. She told us many stories of her adventures ‘on the road’ – during earlier days when some of the roads in Mexico were little more than burro trails. As Bernie relived her memories, her face seemed to lose its weathering, her voice became softer and more youthful. Nor did she dwell upon her vision loss, but after a while she asked us to describe for her what we saw around us that morning – we described the sky, the ocean, its breakers, the frigate birds and pelicans and fishing boats and smoke from the village going out over the bay on the early land breeze – we told her of the recent dolphin and whale sightings - and of last night’s sunset when the whole western sky over the ocean blazed, and as the sun sank into the ocean how a green solar spike had shot skyward.

Bernie was very quiet during our description of nature’s marvels – it was as though she was “seeing” the world through our words – quiet, that is, until Marnie described a butterfly cruising past – Bernie animatedly said that she had completely forgotten about butterflies- it had been so long since she had seen them - and she asked about the creature’s flight and movements. Thereafter, we told her about the amazing trans-generational migratory flight of these creatures from Mexico to Canada and back (see ‘our story’ about the Tao of the Magical Monarchs) and her old eyes glistened at the telling of the butterflies’ migratory flight plan transcending the physical limitations of several generations. Nothing would do but that we promise to re-tell the story on the morrow, when she would return with her cassette recorder.

Sure enough, bright and early the next morning Bernie and Sadie returned. After taping the Monarch nature story for her, I flipped the cassette and entered the story of bat echolocation. – how the bat, while cruising, projects its ultrasonic (above 20 kHz) squeak at the rate of 10 pulses per second, which allows its brain to develop a map which precludes its hitting trees, buildings, etc – but when prey is sensed, the pulse rate goes up as high as 200 squeaks per second as the bat ‘fine-tunes’ the range; that its ears are so delicate they would be destroyed by the outgoing squeak, were their brains not able to pressure constrict their hearing circuits synchronistically – imagine valves in the ears closing up to 200 times per second so as to not be destroyed by the outgoing high-pitched squeak, and reopening 200 times per second so that the returning echoes can be absorbed for analysis and update of the bats’ model of environment and prey. And how after its nightly food flight, the bat is able to hone in on its own frequency to finds its way home to its nest in some cave, or attic. In the enormous Carlsbad Caverns of New Mexico, we have seen the evening departure of millions of bats – yet never saw a mid-air collision. What a marvelous way for nature to provide a living for this mammalian species (dolphins and whales, also being mammals, use variants of this ‘sonar’ system both for guidance and communication).

Bernie later visited us several times - not only during our stay that first year - but in later years on our subsequent trips to the village. It was always amazing to see her navigate around the village and through the coconut grove where we camped. Her dog Sadie was much too small to be of use as a ‘seeing-eye dog”, yet surprisingly Bernie got around almost as easily as ourselves. It was noticed, though, that she was always softly singing, or talking to Sadie as they walked, and one wondered. Later we came across studies indicating that some blind people do learn to train themselves to use a form of ‘echo-location’ – i.e. to train their brains to build sound pictures of their environment using reflected sound. Perhaps that is what Bernie did as she “saw” her way about her beloved Mexico village.

Keith and Marnie

Elliott’s “REMEDY” Site

Home

|

Our Stories

|

The Sublime

|

Our World and Times

|

Book Reviews

|

Marnie's Images

|

The Journal

|

Gleanings

|

From The Writings Of. . .

|

Allegories

|