We here today are the

winners in Life’s lottery – survivors of countless generations that preceded us

in the long arc of life embodiment. The ancestors of all life forms existent

now had to have themselves been the recipients of selective gifts sufficient to

grow to maturity and reproduce, thereby contributing their link in the chain of

continuum leading to today’s edition, here and now. In each generational step –

and long before human biomedicine advances – Mother Nature, through her wondrous

processes, selected those traits that would enhance the probability of survival

of each of her children, and supplied each with a set of adaptive survival

aids. All species existent today possess built-in efficient life management

strategies functioning wisely and automatically, safely hidden beyond conscious

control.

What follows, then, are

the interim results of our ongoing examination of this wondrous bequest,

referenced by the attributed findings of leading thinkers across many disciplines,

with leads to further material for more in-depth study by those interested in…

NATURE’S LIFE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

(What the placebo response tells us)

[A placebo is a simulated or otherwise medically

ineffectual treatment for a disease or other medical condition, intended to trick the subject’s system with information so that it

believes the situation warrants a reduction in pain or the mounting of a

resource-expensive immune response. Often patients given a placebo

treatment will have a perceived or actual improvement in a medical condition, a

phenomenon commonly called the placebo response.]

I said

that the cure itself is a certain leaf, but in addition to the drug there is a

certain charm, which if someone chants when he makes use of it, the medicine

altogether restores him to health, but without the charm there is no profit

from the leaf. (Plato - Charmides).

Our remedies oft in ourselves do lie.

(William Shakespeare - All's Well That Ends Well)

Will science take the mystery out of healing? I don’t

believe so. I think there’s going to be an element of the shaman residing at

the core. My effort to do research in placebo is to acknowledge that core, not

to destroy it, because I don’t think it can be destroyed.

(Ted

Kaptchuk - Co-Director, Program in Placebo Studies, Harvard)

INDEX

THE ALLOPATHIC AND ALTERNATIVE MODELS

THE PLACEBO RESPONSE: EVOKING THE INTERNAL

HEALER

REPORTS FROM TO-DAYS EXPLORERS OF

LIFE’S INTERNAL HEALING MECHANISMS

SETTING THE STAGE:

Our interests in the

mysteries of healing processes deepened in January 1993 by a visit to observe

the curanderos plying their trade in San Juan Chamula, in the Chiapis

Highlands of Mexico, and then in Chichicastenango, Guatemala. The account of

our findings at that time is HERE, and it

attests to the power of belief and intention. Both of us had had secular upbringing

and were blessed with good health, only occasionally having had to resort to

western allopathic biomedical practitioners. We had earlier seen certain Hopi

and Navaho rituals in Arizona, and had often wondered between our selves as to

how our forebears had managed to cope without 19th and 20th

century advances in medical technology, but to actually see with our own eyes

people being ‘treated’ for their afflictions through the apparent agency of

faith, belief and ritual was mind opening. Over the next two years we read up

on shamanic processes and also became aware of many alternative healing

practices and belief systems, almost to the point of bewilderment in that it

seemed virtually anything had been or was currently employed somewhere

in the interest of curing and healing: visualization, chanting, dowsing,

aromatherapy, acupuncture, herbs, reflexology, iridology, fragrances, massage,

yoga, electromagnetic frequency generators, psychotherapy, prayer, Christian

Science, hypnosis, meditation, astrology, therapeutic touch and more.

The issue of health

attracts a lot of interest, and thus it is that there are many means toward the

same ends as that promised by traditional allopathic biomedicine, namely the

triggering of an afflicted person’s internal curing-healing mechanisms. In 1995

we traveled extensively, and amongst our experiences was a visit to Boston

‘Mother Church’ of Christian Science (where we had privileged discussions with

adherents from as far away as Australia),followed by a week in Salt Lake City

interacting with the LDS Mormons. That year we also spent two months combing

the archives of the Association for Research and Enlightenment (A.R.E.) in

Virginia Beach. (1)

What follows, then, are

the findings and reflections of two questers who are deeply in love with each

other, and with life; and just as any lover wants to know more of the beloved,

we are deeply curious about the vital forces of Nature, and attentive to the messages we pick up from the natural world. We live in a part of the

world that experiences the four-season effect – where nature cycles its

creatures through the perennial birth-maturation-contraction-dormancy

progression – the seed preserved to flower again at the sun’s bidding. It is

hard to imagine that all came about as a result of chance – the natural world

itself whispers of an implicit intelligence guiding the evolution of explicit manifestations of

itself, adapting to greater complexities and richer diversities. Just as we

look to our past to better understand our now, we naturally

project the arc into the future, and wonder… Yet the wonder also

embraces our realization that – within the beauties of beloved life – there are

harsh rigors involved in the birthing and recycling processes – and those

rigors attend the existence of the transient sun,

stars and galaxies, as well as continuance of all sentient life. Not being

certain as to the meaning of the Mystery, we can grant ourselves permission to

explore all possibilities, and wonder…

It was early January 1998, and they’d been back in Mexico for a

couple months, currently camping in their Coleman pop-up in a primitive sandbar

campground adjacent the fishing village of La Manzanilla, parked in a coconut

grove directly adjacent the Pacific Ocean. They’d been here on previous trips,

and as a result knew many of the other snowbird campers and local residents and

shopkeepers … some of their experiences in this delightful place are to be

found HERE , HERE and HERE.

Each dawn commenced with a 10km walking circuit, the return leg

of which was especially anticipated since it was along the beach back to the

camp and breakfast, and along the beach there might be an opportunity to

observe schools of sea bass cruising across the face of large incoming waves,

or sometimes a whale breaching further out in Bahia Tenacatita. One morning

before moving onto the beach he stepped into a grove of mesquite to have

a pee, and there was quite shaken to observe that his stream was coloured a

high crimson. His immediate thought was that it might be cancer, his mind

linking the symptom to a life-threatening incidence inflicted upon their eldest

son the prior year. It seemed that his energy emptied out of him along with the

fluid, and he was quite introspective during the remainder of that morning’s

walk. Later in the day, a sample of urine was shown to the lady doctor in the

fishing village, and she recommended an immediate consultation with specialists

at a private clinic-hospital in the city of Manzanillo, some 60 km south.

That afternoon they presented at the clinic, and perhaps because

of their touristo appearance (and hence probably representing an

insurable opportunity) they were quickly moved past the dozen or so Mexicanos

already queued in the reception room and – while a urine sample was being

analyzed by the clinic technicians – a very eager urology specialist who

fortunately was fluent in English conducted an interview. The urologist then

gravely perused the lab report, and he indicated that – in his professional

view – there was blood in the hombre’s urine. Seeing that we were all in

agreement thus far, he prescribed a strong laxative to be taken that day so as

to clean out the afflicted body overnight, followed by fasting until a

scheduled return visit the next morning when the urologist would administer an

IVP (intravenous pyelogram). This procedure comprised a dye inserted into a

vein, followed by the taking of an hour-long time-lapse series of X-rays to

image the urinary tract as it processed the dye and also to reveal any

obstructions in the system. Following the IVP procedure, the urologist

explained through graphics and the X-rays, what had occurred… the prostate

gland at the base of the bladder had became very enlarged over time, creating a

convexity in the bladder floor that had kept urine from being expelled, and in that

residue of urine, a quantity of stones had formed. A large quantity – 40 or so

showing on the X-rays – and apparently one of the stones had rattled against

another and split, with a piece then being small enough to enter and cut the

exit urethra on its passage the previous morning in the mesquite patch.

The Mexican urologist indicated that standard treatment called

for a downsizing of the prostate via TURP

– trans-urethral-resection of the prostate (essentially a roto-rooting

hollowing of the gland), and then a manual crushing of the stones and flushing

of the fragments – the whole procedure performed by going up through the

waterworks from outside. The urologist also noted that recovery rooms were

available at the hospital, since there would be post-procedural incapacitation

for a few days. He also advised that the patient’s insurance would take care of

the expenses, and that the procedure should be undertaken ASAP as otherwise

recurrence of the symptom could lead to infection. Perhaps it was weakness from

loss of blood, or from the purgative-fasting regime, or wariness from having

observed the peeling paint on the ceiling whilst undergoing the X-rays, or

simply being a Canuck chicken … but the thought arose that there must

be a better way, and our hero suddenly recalled (falsely) that his retirement

medical insurance was only valid domestically rather than abroad, so he would

have to take a rain-check to ponder the options. The urologist was obviously

disappointed, but on the settling of his account for services rendered over the

two visits, he agreed to release the X-rays for further study and possible

early reconsideration and return, or otherwise for assessment by doctors back

home.

It was another three months before the couple returned home,

after a second two month stopover in Virginia Beach to comb the A.R.E. archives

for leads on an earlier interest in electromagnetic (E-M) fields and energy

medicine, and along the way a few stones had been passed and retrieved. Another

month passed while being processed through the family doctor-urologist system,

another month in lab tests on the stones to determine composition, and a couple

months in delaying discussions with the urologist (Dan - not his real name). It

was recalled that both of the patient’s older brothers had underwent the TURP

procedure with serious, enduring post-op complications such as urinary

incontinence, sterility and impotence, complications that – Dan admitted – were

highly probable … but the stones had to come out, and they’d quickly re-form in

the bladder unless the prostate was downsized. In the meantime, Dan arranged

ultrasound imaging to calibrate the prostatic volume, and he also personally

examined the prostate-bladder via cystoscope, at the conclusion of which he

exclaimed to the attending nurse that “this bladder’s so full of stones it

looks like a bubble-gum machine”.

Ever since the January incident, the couple had been personally

researching alternative options, including discussions with homeopathic,

acupuncture, herbalist and naturopathic practitioners. They’d also continued

their main research of recent years, tracking down literature and contacts

pertaining to the electromagnetic work of Robert O. Becker, the extensive research by Professor Michael Persinger concerning magnetism and the brain,

the biofeedback-GSR studies of Elmer and Alyce Green and – following on a lead at A.R.E.,

they tried to locate a Danish-born, Toronto based electrical engineer and

inventor of numerous devices including a cigarette-pack sized 8 hertz pulsed

magnetic-field generator that ran on a nine volt battery and was used to

stabilized brain waves at the alpha state, inducing emotional and physical

well-being. This inventor was eventually tracked to his retirement home in a

community approx 100 kms away, and when he was telephoned and our interests

explained, he indicated that his inventions and related literature could be

accessed at his wife’s clinic in their nearby market town. We contacted his

wife Alice (not her real name) and drove over to view the products.

Our initial interest was deflected when we noticed that a rear

wall of Alice’s large office was taken up by a bank of five wooden cabinets on

which lights were blinking and several dials affixed, and from which a soft hum

emanated. In response to our queries, Alice indicated that these were radionic machines, and the devices were calibrated

so as to remotely treat her clients, some of whom were relatives as far distant

as Germany and Australia. The technology had been invented in the early 1900s

by a California alternative health practitioner n/o Albert Abrams who claimed

that a person normally maintains organic health through the brain’s employment

of discrete signals to each organ – each of which operates within its own

unique frequency range; for example all human livers respond to a ‘liver’

frequency, adjusted slightly because each body itself is unique. Disease or

dysfunction occurred when the brain’s guiding ‘signal line’ to its organs is

lost. Seeing that all parts of a body contain a record of the whole, diagnosis

and remedial treatment could be effected through a representative ‘witness’

from the host body, such as a hair clipping, blood sample, or nail clipping

which was placed in a ‘witness-well’ of the device. All but one of the device’s

dials would be set to the prescribed ‘frequency rates’ determined by Abrams

from tests on healthy subjects. The setting for the final dial was determined

through a focused dowsing operation by the operator who visualized the known

patient and – in stroking a rubberized ‘stick-pad’ whilst simultaneously

rotating the final dial – tuned in on the unique DNA frequency of the subject,

as represented by the ‘witness’… and started incrementally nudging the

dysfunctional organ to its generic rate.

[Some understand the rates as access codes to groups of

energy information patterns, themselves complex frequencies resonant with the

subtle energy fields of specific tissues, organs or pathologies – and that the

‘radionic’ phenomenon itself is a means of information transfer that informs

the patient’s system as to what it needs to bring itself into harmony. Others

believe the essence of radionics comprises the unity of operator and subject,

established by intent and facilitated by an instrument, and that the

fundamental activity behind the application of radionics is the operator’s

handling of consciousness.]

Alice was advised about the ongoing EM studies and the ARE

research, it also being mentioned that we’d came across references to Abrams

and radionics, but had thought that the process had been abandoned, and we’d

never expected to encounter an actual practitioner. Alice observed that she

herself had been an R.N. many years ago, but she’d developed cancer that

oncologists had diagnosed as terminal; she’d refused surgery/ radiation/ chemo

etc and healed herself through adjustment of life-style, visualizations and

treatments by a radionics practitioner. She had somehow managed to acquire an

‘Abrams box’ and her husband had replicated the device for use in her own

clinic, and he’d also made devices for the use of her students in their own

clinics in other communities.

She provided a list of authors dealing with the field, and we

subsequently accessed many of these books for our research. On the spur of the

moment, Alice was asked if she’d ever treated any patients for bladder stones

or enlarged prostate, and she was shown the Mexican X-rays and local ultrasound

and lab reports which for some reason had been dragged along; she answered in

the affirmative as to prostate, but in the negative as to stones - then checked

her Abrams rate book and said there was a rate indicated for stone elimination.

She said that – should radionic treatments ever be requested - the first couple

should be handled here in her office, with the patient sitting across the room

reading or whatever, where she could watch for any untoward reactions during

treatment; also the client should be accompanied by another person to drive him

home, as sometimes deep fatigue would be experienced afterwards. Later

treatments could be conducted remotely on demand, with the caveat about

subsequent weakness and fatigue as the client’s body readjusted.

A few weeks later and after research, Alice was contacted, a

hair sample given, and for the next hour her treatment procedures were observed

from across the room, with no wiring connected to the body. Alice applied

herself silently in very purposeful concentration and her confident,

professional approach bespoke of belief and intention in the same manner as

that earlier seen in the curanderos of Central America. Marnie was quite

interested in the process, and Alice showed her how the stick-pad worked. No

effects were felt during the treatment, but on the way home he was glad to not

be driving, and mainly slept then … and for the rest of that day.

Four days later (Oct 18th) Dan telephoned and said

that – after reviewing the file – he felt that he should perform a biopsy of

the prostate on the 20th, to ensure there was no malignancy. This

would be undertaken on an outpatient basis under full anesthetic, and since it

appeared to be a reasonable precaution, the procedure was booked. After the

biopsy, a second visit to Alice’s clinic occurred on Oct 30th, and

she was apprehensive concerning the biopsy, as colour had by then reappeared in

the urine. After treatment, he again slept on the way home, and the next day

was totally exhausted, with bladder spasms later commencing and attempts to

urinate every 15 minutes.

Over the next two days the spasms intensified and then

disorientation set in; by evening of the 4th day of blockage we went

to ER for catheterization. The ER staff was unable to insert a catheter, and

Dan was called in and finally he was able to force in a catheter; he expressed

his exasperation at the foot dragging to proceed with the TURP, and he was told

that the reason stemmed from concerns over the procedural side-effects; that

the physical expression of our love for each other was a most important aspect

of our lives; and that – even with the cramps etc. – last night we had made

love for possibly the last time and later wept together. Dan’s professionally

detached composure crumbled with empathy, and he said that he should

immediately schedule the TURP, but that he would modify the procedure to leave

sufficient prostatic tissue at the upper end to retain normal bladder sphincter

function.

About a week

later Dan performed the modified TURP. An epidural anesthetic allowed actual

observation of the resection and subsequent pulverization of the stones –

one-by-one – via laser lithotripsy. Afterwards, Dan came by the recovery room,

and – after providing assurances that everything had went as agreed – he

admitted to being very perplexed, saying “notwithstanding the X-ray

images and my own earlier scoping to fully evaluate the situation, plus

ultrasound imaging to measure prostate size, my findings during the actual

procedure were (i) the prostate was only half the expected size, and (ii) there

were only half as many stones present, and they were much smaller than

expected. So… do you have any idea as to what has happened??”

To which

there was no response, yet one could wonder…

THE ALLOPATHIC AND ALTERNATIVE MODELS

The western allopathic bio-medical infrastructure

in place today was mainly designed with infectious agents in mind. Physician

training and practices, hospitals, the pharmaceutical industry and health

insurance all were built around the model of running tests on sick patients to

determine which drug or surgical procedure would best deal with some discrete

offending agent. The model worked well for its original purpose, but medicine’s

triumph over infectious disease brought to the fore the so-called chronic,

complex diseases – heart disease, cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s and other

illnesses without a clear causal agent eg. 365 categories of pharmaceutically

treatable dysfunctions described in the evolving editions of The Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Now that we live longer, these typically

late-developing diseases have become our biggest health problems, and account

for three-quarters of health-care spending.

The

medical community knows that preventive action is the way to go – and aside

from getting people to stop smoking – the three most effective ways of lowering

the risk that these diseases will take hold in the first place, are the

promotion of a healthy diet, encouragement of more exercise, and measures to

reduce stress; these practices do a better job of preventing, slowing, and even

reversing heart and other diseases than most drugs and surgical procedures. To

get patients to make the lifestyle changes that appear to be so crucial for

lowering the risk of serious disease, requires practitioners to lavish

attention on them, which means longer, more frequent visits; more focus on

what’s going on in their lives; more effort spent easing anxieties, instilling

healthy attitudes, and getting patients to take responsibility for their own

well-being; and concerted efforts by the practitioner to create emotional bonds

with patients. Through these practices, the practitioner conveys to his

patients his enduring commitment to care for them over time, which imbues the

patients with trust, hope, and a sense of being known.

As

Hippocrates said “It is more important to know what sort of person has a

disease than to know what sort of disease a person has.”

Practitioners

of both biomedicine and alternative/ complementary models emphasize what they

do, and how that makes a difference, with an accompanying explanatory framework

over which practitioners of differing stripes can argue endlessly. Yet beyond

the squabble, lies the fact that health is much more than either biomedicine or

alternative medicine: Health is something onto itself. The allopathic

biomedicine model has privileged surgical procedures and pharmaceuticals, with

doctors doing something or giving something to the patient. Even

with preventive biomedicine, the emphasis is on the doctor issuing the

right set of recommendations – the right intervention – that will make a

difference. The biomedicine model focuses almost exclusively on finding and

evaluating techniques of intervention, rather than on factors like

environments, relationships and meanings, whilst it is more often in the

various modalities of alternative/ complimentary therapies that these latter

aspects are addressed. Just as in the time of the medicine man, shaman and

kahuna, in both of today’s models there are symbols of authority (white coat,

diplomas, prescription pad) and ritual (supplication, diagnosis, prescription

and the power of suggestion from authority).

Generally,

people that DON’T believe in the treatment that they are getting, DON’T do as

well. If they don’t think it’ll make a difference, usually the effect of any

intervention is diminished. Understanding how people come to accept a

particular medical system is an interesting area to study. As decades of

research in medical anthropology has shown, patients need to buy into the local

treatment system for them even to want to access it. Medical practitioners

often employ elaborate persuasive processes to heighten and project their

perceived authority and to compellingly substantiate their diagnoses of

patients’ illnesses (and also to later explain away any treatment failures).

Belief in the treatment model and in the practitioner certainly matters, as

does consensual agreement between the practitioner and the patient as to what

is to be expected in the individual’s healing.

THE PLACEBO

RESPONSE: EVOKING THE INTERNAL HEALER

Medical

practitioners are part-time magicians, and in accordance with tradition the

doctor manipulates the setting and the stage to achieve ‘white magic’ via

placebo (as opposed to nocebo effect, wherein the patient, not

believing, is not healed by legitimate medicine). (Ivan Illich)

There

is a phenomenon in the healing process whereby a totally inert, sham ‘remedy’ brings

about relief and cure of an afflicted person’s symptoms. This phenomenon is so

statistically robust, that – as repeatedly determined in double blind control

tests – it accounts for 30-50% cure rates. The name given to this function is

the placebo response, and so reliable is it that pharmaceutical

companies must control for it and prove that their products have significant

curative potency above and beyond the placebo response to qualify for licensing

and commercialization of their products.

Dr. Henry K. Beecher, an American anesthetist during World War II, is

considered by many to be the father of contemporary placebo research. Dr.

Beecher assisted in surgery during the Allied campaigns in North Africa, Italy

and France. In one battle his battalion was cut off from any supplies, with 225

soldiers having severe wounds, which caused a morphine shortage. In order to

ration the morphine, Dr. Beecher went up to each soldier and asked how intense

the pain was felt by the soldier. To Beecher’s surprise, although these

soldiers had shrapnel and bullet wounds, three-quarters of them perceived so

little pain that they did not ask for pain relief. Further, it wasn’t that the soldiers were in a state of shock, nor unable to

feel pain; indeed, they complained when the IV lines were inserted. Beecher was

surprised because – compared to his experience in civilian practice – civilian patients with

equivalent injuries had reported much greater pain than these wounded soldiers.

Later, Beecher came to understand that the difference between the two groups as

to apparent pain perception wasn’t because of the mental strength of the

soldiers, but rather it was due to the context of the pain.

The meaning attached to the injuries by the respective members

of the two groups affected their perceptions. To the soldier, the wound meant surviving the

battlefield and returning home, while the injured civilian often faced the

personal expense of major surgery, loss of income, diminishment of activities,

and many other negative consequences. These added stresses amplified the civilian’s

pain, whereas the soldiers’ thoughts filtered out most of the pain.

Ultimately Dr. Beecher concluded that the reality of the wound was not the same

as the perception of associated pain; that drugs work because they are able to

connect to receptors in the brain; and that placebos work because rather than

an active drug having entered the body from outside, the patient’s own body has

created the necessary curative chemicals on its own.

As a result of his continuing research, by 1955 Beecher was admonishing other researchers to

pay attention to the negative aspects of intention, expressed as a ‘nocebo’

effect, saying:

“Not only do placebos produce beneficial results, but like other

therapeutic agents they have associated toxic effects. In consideration of 35

different toxic effects of placebos that we had observed in various of our

studies, there is a sizable incidence of such effects attributable to the

placebo.”

Over the ensuing 50+

years, the fascinating field of placebo research has revealed that the body’s

resilience repertoire contains a powerful self-healing network that can produce

natural analgesics such as dopamine to reduce pain and inflammation, and other

endogenous neurochemicals that reduce production of stress chemicals like

cortisol and insulin and even naturally regulate blood pressure and the tremors

of Parkinson’s disease. Jumpstarting this self-healing network often requires

nothing more or less than a belief that one is receiving effective treatment –

in the form of a pill, a capsule, talk therapy, E-M frequency, injection, IV,

or acupuncture needle. The activation of this self-healing network is what is

really meant in reference to the placebo response. Though inert in themselves,

placebos act as passwords between the domain of the mind and the domain of the

body, enabling the expectation of healing to be in turn translated into

cascades of neurotransmitters and altered patterns of brain activity that

engender health.

Over the years, perhaps one of the strangest

situations involving the placebo effect was that experienced by the London,

England anesthesiologist, Dr. Albert Mason. One of Mason’s jobs

was delivering babies; he wanted to explore different ways to relieve the pain

of his patients, so he began to practice medical hypnosis, and delivered 26

babies through hypnosis alone. The hospital staff became very intrigued by this

and allowed Mason to attempt hypnosis to cure patients with all kinds of

aliments. Mason found that his hypnosis was also very effective in curing

warts.

One day a 15 year old boy arrived covered with

millions of warts all over his body which made his skin look like an elephant’s

hide. The hospital doctors were unable to help the patient, and Mason asked if

they had attempted hypnosis. The head surgeon sarcastically remarked, “Why

don’t you try,” which is exactly what he did. He hypnotized the boy and

told him that his left arm would be clear of the warts. After a week the boy came

back to the hospital and his entire left arm was clear. Mason took the lad to the surgeon and showed him the

arm, and said to him, “Well, I told you the warts would go.” According to

Mason, the surgeon said “This is not warts you bloody fool, this is a condition

called congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma. It’s congenital and

incurable.” Mason believes that this was the point when he lost his ability to heal

congential ichthyosis, because after that meeting he was never able to cure

another patient of that disease.

Mason eventually quit his position at the

hospital and later became a psychiatrist. He eventually came to believe that

the placebo effect was able to work both ways during his hypnosis. He could

introduce the idea to his patients that they would get better, but when he was

himself informed that the disease was “incurable” he subconsciously became

unable to perform hypnosis. He has

written many papers and reviews but is perhaps best known for his paper on

hypnotism in which he suggests that the influence of the hypnotist on the

patient requires a shared delusional system, a folie a deux.

- - - - - -

Scientists have

recognized for some time that people suffering from depression often experience

a substantial reduction in symptoms when given a placebo. In fact, this

observation has led some researchers to propose that up to 75 percent of the

apparent efficacy of antidepressant medicine may actually be attributable to

the placebo effect. People want/ hope to be relieved of their depression

suffering, and submit to the healer’s ritual. The results of a 2002 study (2) by a team of researchers led by Dr. Andrew Leuchter at the Psychiatry and Biobehavioural Sciences Dept., UCLA noted that depressed patients responding to placebo treatment

exhibit a change in brain function, but one that differs from that seen in

patients who respond to pharmaceuticals.

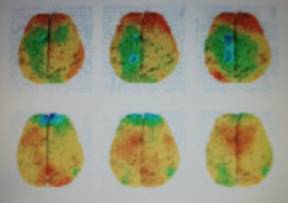

Using

quantitative electroencephalography imaging, the UCLA team studied electrical

activity in the brains of 51 depressed patients receiving either placebo

treatment or active medication. In patients responding favorably to the

placebo, there was increased activity in the prefrontal cortex region of the

patients’ brains. In contrast, those responding to pharmaceutical medication,

exhibited suppressed activity in that area.

The

image shown here illustrates changes in prefrontal cortex activity over time in

the placebo responder group (top row) and in the medication responder

group (bottom row): with red indicating an increase in brain activity

and blue-green representing a decrease.

Dr. Leuchter noted

"Both treatments affect prefrontal brain function, but they have distinct

effects and time courses… The results show us that there are different pathways

to improvement for people suffering from depression. Medications are effective,

but there may be other ways to help people get better and if we can identify

what some of the mechanisms are that help people get better with placebo, we

may be able to make treatments more effective.”

[Compilers’ observation: when placebo was administered and the

patient’s Internal Healer was evoked, the brain’s frontal cortex (the

organizing, rational Executive function) was activated, rather than

being suppressed by exogenous pharmaceuticals.]

Perhaps

rather than considering the placebo response solely as a phenomenon of

belief-constructs, it would be closer to the mark to consider the process as

one of asking for – and receiving from the therapist – permission to heal one’s

own body (or mind). Perhaps the patient simply gains sufficient assurance

from the therapist’s attempts to treat him, that he can consider himself to be

sufficiently worthy to proceed with activation of his Internal Healer.

Evidence-based

biomedicine has worked hard to put a great deal of distance between itself and

the “magical side” of the art of medicine, but the controversy over the placebo

response implies that it is hard to entirely escape this ‘magical side’. The

placebo effect smacks of faith healing and other practices that look blatantly

superstitious to science-based practitioners. The other side of the coin – the

so-called nocebo effect – tilts all too closely in many minds to sorcery, black

magic and witchcraft. When searching for diagnostic techniques and treatments

for the diseases and organic problems of their patients, practitioners of

evidence-based biomedicine are not deeply concerned with what meaning a

patient perceives in how the illness began or how it’s being treated – unlike

the primary concerns of shamans, curanderos and healers of other medical

traditions across millennia of time.

The

science-based biomedical model with its highly rational approach to diagnosing

and curing diseases and in its emphasis on biological reductionism has

instilled in its practitioners a cultural “blinder” or bias against the

holistic approach. Because of the personal and cultural beliefs of patients and

their search for the meaning of their suffering, many patients resist reducing

their maladies to physiological malfunctions, and they appreciate practitioners

willing to pay attention to their own narrative of the illness and its meaning

to themselves. This narrative may not be rational from the perspective of an

evidence-based doctor – especially if there are significant cultural

differences between patient and doctor – but the narrative may be very

logical when viewed within another framework, one with an alternate set of

basic assumptions regarding the nature of reality. Different logics, after all,

are based on different assumptions, and what isn’t logical in one context may

be very logical in another. The meaning narrative – when accepted by

sufferer and other – may precede a positive response to a symbolic placebo –

perhaps some sacrament, or transcendental contact with the sacred, or a ritual

that evokes faith in something beyond the ordinary – and opens the conduit

through which the Internal Healer may emerge. Sensitive responses by healers to

the common human desire for meaning may trigger the patient’s Internal Healer

in ways that external interventions based on evidence-based medicine couldn’t.

CAVEAT:

Dr. Dean Ornish of UCSF notes, “75 percent of the $2.6

trillion the U.S. spent on health care was for treating chronic diseases that,

to a large degree, can be prevented or reversed through lifestyle change”.

Thus notwithstanding our earlier observations and pragmatically bearing in mind

systemic revenue interests, there is a recognizable conflict of interest

inherent in the illness industry. It just wouldn’t make sense to expect

physicians – who, after all, have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars and a

decade of their lives becoming trained in anatomy, biochemistry, high-tech

diagnosis and pharmacology, etc – to spend long blocks of time bonding with

patients and helping them empower themselves through becoming more self-reliant

on their internal healing mechanisms, thereby weaning themselves off exogenous,

cross-indicating pharmaceuticals. Professionals in a medical system that

successfully guided patients toward healthier lifestyles would almost certainly

experience dramatically reduced cash flows. Also, the pharmaceutical business is, after

all, a business, and companies are supposed to boost sales and returns to

shareholders, so it is common knowledge that drugmakers make sure that the

researchers and doctors who extol the benefits of their medications are well

compensated. Who, then, aside from the

patients, has any tangible incentive to make changes that would remove monies

from the health care system?

REPORTS FROM TO-DAYS

EXPLORERS OF LIFE’S INTERNAL HEALING MECHANISMS

F Irving Kirsch - lecturer in

medicine at the Harvard Medical School and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical

Center), and Associate Director of the Harvard Program in Placebo Studies - PiPs*

As an outgrowth of his interest in the placebo

effect, Professor Kirsch performed extensive analyses of the real effectiveness

of antidepressants. His studies were primarily meta-analyses, in which the

results of previously conducted clinical trials were aggregated and analyzed

statistically. His first meta-analysis – limited to published clinical trials –

was aimed at assessing the size of the placebo effect in the treatment of

depression: the results not only showed a very sizable placebo effect, but also

indicated that actual effects of the active drug itself was surprisingly small.

This naturally led to considerable controvery, whereupon Kirsch shifted his

focus to evaluating the antidepressant drug effect through obtaining files from

the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) containing data from trials that

had not been previously published, as well as those from

published trials.

[It should be here noted that to gain FDA

licensing approval to market their products, pharmaceutical companies are

required to produce trial results showing that a product performs better than

placebo; the kicker is that they can run x number of trials, yet

only submit those trial results showing favorable results.]

Kirsch’s meta-analyses of the FDA data showed

that the difference between antidepressant drugs and placebos is not clinically

significant according to the criteria used by the National Institute for Health

and Clinical Excellence (NICE), which establishes treatment guidelines for the

National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom.

As a result of his analyses, Kirsch developed the

response expectancy theory, which is based on the idea that what people

experience depends partly on what they expect to experience. According to

Kirsch, this is a major part of the process that lies behind the placebo effect

and also hypnosis. The theory is supported by research showing that both

subjective and physiological responses can be altered by changing people’s

expectancies, and it has been applied to better understanding pain, depression,

anxiety disorders, asthma, addictions, and psychogenic illnesses.

Kirsch argues (3) that the widely-held theory that depression is caused by

a chemical imbalance is wrong:

"It now seems beyond question that the traditional account of

depression as a chemical imbalance in the brain is simply wrong … and the kinds

of effects you see in the brain when people respond to a placebo depends on the

condition you’re supposed to be treating. So if you take a placebo analgesic,

you get reductions in activity in the brain’s pain matrix. If you take a

placebo antidepressant, you get changes in brain activity in areas related to

depression.”

In

his own placebo experiments, Kirsch prepped volunteers by informing them that

placebo effects work via classical conditioning, like Pavlov’s dogs being

trained to salivate at the sound of a bell. He reported “people all over the world respond to the act of taking a pill when

informed of the existence of prior successful treatments. People come to expect

and believe that they’re going to get better if they take medication. The whole

process of going to a physician and being treated reinforces this belief, and that

constitutes the basic aspects of classical conditioning. Eventually, the pill

alone is enough to produce a placebo effect, whether it contains an active drug

or not.”

Kirsch

also indicated that “direct-to-consumer drug

advertising also plays a role; e.g. it has been proven in meta-analyses of

anti-depressants that none of them perform better than placebos, yet in the

anti-depressant market in America, when you open a magazine, the good-looking

jock playing with puppies in the sun is the formerly depressed patient on

Zoloft. One thing that’s clear is that the placebo effect of antidepressants

has gotten stronger over the years as these drugs have been more widely

accepted, touted, and advertised… We have the capacity for healing physical

conditions through psychological means.

There

used to be an ethical concern in the medical profession as to a doctor

presenting a placebo that he knew was inert, to a patient who in effect had been

deceived into believing the pill was medically active. According to Kirsch (3) “that no longer has to be a concern, since now we know that the placebo

effect still works even when people know they’re taking placebos. That’s one of the nice things

we’ve learned from these studies. Plus, there’s an ethical problem when you

keep secret the fact that you’re giving someone a drug that barely works –

especially when the drug has harmful effects as well… These studies suggest

that in the brain, belief is a two-tiered process: one that knows there’s

nothing in this pill, and another that knows that a placebo can be an effective

treatment. It’s as if the brain can entertain two different notions of the

effectiveness of a pill at once… these are not contradictory notions. I believe

in both. I know that this pill does not contain a physically active ingredient,

and I also understand the conditioning process. I know that the placebo effect

is real, so I understand that this inert pill might help trigger that healing

response within me. We need to recognize and understand that patients are

active agents in their treatment, not passive. The placebo effect does not come

from the pill. It comes from the patient.”

Quotes

from Irving Kirsch’s landmark book - The Emperor's New Drugs: Exploding the

Antidepressant Myth (4)

“Depression is a serious problem, but drugs are not the answer. In

the long run, psychotherapy is both cheaper and more effective, even for very serious

levels of depression. Physical exercise and self-help books based on CBT can

also be useful, either alone or in combination with therapy. Reducing social

and economic inequality would also reduce the incidence of depression.”

“Our analyses of the FDA data showed relatively little difference

between the effects of antidepressants and the effects of placebos. Indeed, the

effects were so small that they did not qualify as clinically significant. The

drug companies knew how small the effect of their medications were compared to placebos,

and so did the FDA and other regulatory agencies. The companies found various

ways to make the data seem more favorable to their products, and the FDA helped

them keep their negative data secret. In fact, in some instances, the FDA urged

the companies to keep negative data hidden, even when the companies wanted to

reveal them. My colleagues and I hadn't really discovered anything new. We had

merely revealed their 'dirty little secret'.”

“Physicians do not systematically prescribe placebos to their

patients. Hence they have no way of comparing the effects of the drugs they

prescribe to placebos. When they prescribe a treatment and it works, their

natural tendency is to attribute the cure to the treatment. But there are thousands

of treatments that have worked in clinical practice throughout history.

Powdered stone worked. So did lizard's blood, and crocodile dung, and pig's

teeth and dolphin's genitalia and frog's sperm. Patients have been given just

about every ingestible - though often indigestible - substance imaginable. They

have been 'purged, puked, poisoned, sweated, and shocked', and if these

treatments did not kill them, they may have made them better.”

“Like antidepressants, a substantial part of the benefit of psychotherapy

depends on a placebo effect, or as Dan Moerman calls it, the meaning

response. At least part of the improvement that is produced by these

treatments is due to the relationship between the therapist and the client and

to the client's expectancy of getting better. That is a problem for

antidepressant treatment. It is a problem because drugs are supposed to work

because of their chemistry, not because of the psychological factors. But it is

not a problem for psychotherapy. Psychotherapists are trained to provide a warm

and caring environment in which therapeutic change can take place. Their

intention is to replace the hopelessness of depression with a sense of hope and

faith in the future. These tasks are part of the essence of psychotherapy. The fact

that psychotherapy can mobilize the meaning response - and that it can do so

without deception - is one of its strengths, not one of its weaknesses. Because

hopelessness is a fundamental characteristic of depression, instilling hope is

a specific treatment for it. Invoking the meaning response is essential for the

effective treatment of depression, and the best treatments are those that can

do this most effectively and that can do so without deception.”

[See footnote (4) for link to further Kirsch quotes]

F Ted J. Kaptchuk - Associate

Director of the Harvard Program in Placebo Studies - PiPs*

From “Placebo studies and ritual theory: a

comparative analysis of Navajo, acupuncture and biomedical healing” by Ted J. Kaptchuk (5)

“Taken as a whole, the study of placebos illuminates theory in

several concrete ways. Minimally what has been found includes:

·

Rituals have

neurobiological correlates. This suggests that patient improvement is not only

report bias or desire to please the healer but represents changes in

neurobiology. Specific areas of the brain are activated and specific

neurotransmitters and immune markers may be released.

·

Biomedical

treatment with powerful medications has a ritual component that is clinically

significant.

·

As with

pharmaceuticals, each type of ritual, for example, fake needles versus fake

pills, has a unique outcome.

·

Components

of rituals can be disaggregated and incrementally combined in a manner

analogous to a dose response. For example, adjusting components of a ritual

could make it more or less persuasive.

·

When

engaged in a ritual, patients do not abandon practical sensibilities. Hope,

openness and positive expectancy are tempered with uncertainty and realistic

assessment.

·

Different

healers can have different effects on patients even when they perform an

identical, prospectively-defined, precise, scripted interaction.

“At a minimum, healing rituals provide an opportunity to reshape

and recalibrate selective attention. In a more expanded model, rituals trigger

specific neurobiological pathways that specifically modulate bodily sensations,

symptoms and emotions.

It seems that if the mind can be persuaded, the body can sometimes

act accordingly. Placebo studies may be one avenue to connect biology of

healing with a social science of ritual. Both placebo and ritual effects are

examples of how environmental cues and learning processes activate

psychobiological mechanisms of healing.

In conclusion, for biomedicine the ‘placebo

effect’ has been primarily of interest as a non-specific process that needs to

be controlled. In contrast, for ritual theory, the placebo effect is the

specific effect of a healing ritual. Combining placebo studies with ritual

theory can help provide a conceptual shift to counteract the ideological

devaluation of ritual in biomedicine. The linkage of ritual theory and placebo

studies can expand the discourse of both fields.” (5)

From ‘‘Maybe I Made Up the Whole Thing’’: Placebos and

Patients’ Experiences in a Randomized Controlled Trial” (6):

“Interviews of the 12 qualitative subjects who underwent

and completed placebo treatment were transcribed. We found that patients:

(1) were persistently concerned with whether they were receiving

placebo or genuine treatment;

(2) almost never endorsed ‘‘expectation’’ of improvement but spoke

of ‘‘hope’’ instead and frequently reported despair;

(3) almost all reported improvement ranging from dramatic

psychosocial changes to unambiguous, progressive symptom improvement to

tentative impressions of benefit; and

(4) often worried whether their improvement was due to normal

fluctuations or placebo effects.

The placebo treatment was a problematic perturbation that provided

an opportunity to reconstruct the experiences of the fluctuations of their illness

and how it disrupted their everyday life. Immersion in this RCT was a

co-mingling of enactment, embodiment and interpretation involving ritual

performance and evocative symbols, shifts in bodily sensations, symptoms, mood,

daily life behaviors, and social interactions, all accompanied by self-scrutiny

and re-appraisal. The placebo effect involved a spectrum of factors and any

single theory of placebo – e.g. expectancy, hope, conditioning, anxiety

reduction, report bias, symbolic work, narrative and embodiment – provides an

inadequate model to explain its salubrious benefits.”

[Compilers’

observations as to the four Kaptchuk et al findings]

1 – uncertainty gives rise to the patient’s co-effort vs.

dependency state

2 – hope instead of expectation introduces the

‘Doubt’ aspect; Doubt opens the patient’s ‘self-permission to heal’ aperture

3 – attention from another in the treatment ritual

stimulates the perception by the patient’s of his ‘worthiness-to-improve’ on

various levels

4 – again, doubt allows the ‘permission>self-cure process’ to

cycle

“The emergent

neuroscience hypothesis of ‘prospection’ provides another way of thinking about

our findings concerning ‘expectation’ and ‘hope’. ‘Prospection’ proposes that

people constantly build simulations of the future in their minds to explore

different future scenarios. This multiplex theater operates as a stage

or representational space whereby simulations of the future can be

constructed and explored. A proposed detail of this constructional space is

that it allows a representation of current reality and also secondary

representations that explore future possibilities’’ (Buckner 2007). From this

point of view, our patients are seen to have engaged in a dynamic process that

entertained multiple possibilities of the future (and even the present).

Prospection allows for such multiple possibilities, which could include

improvement, worsening and little change. Hope seems aligned to this notion of

prospection and represents openness to multiple outcomes including

amelioration.

Still another, more anthropological rubric for the examination of

‘expectation’ and ‘hope’ is the concept of ‘subjunctivity’ of illness

narratives, a concept that medical anthropology borrowed from the field of

literary criticism. In telling (or thinking) the story of their illnesses,

especially chronic illnesses, individuals are often careful to indicate some

uncertainty, if not frank hope, as to the anticipated future course. Theorists

of ritual have noted that this subjunctive ‘as if’ framework can actually pull

someone into a deeper level of participation and somehow ‘make the illusion the

reality’

… what began as an ‘‘as if’’ subjunctive interpretation of

experience later became the premise for a construction of a healing encounter

built on enactment, embodiment and interpretation – ultimately experienced as

healing…

The context of an acupuncture regime might not generalize to

patients who undergo more

familiar, conventional medication pill therapy. Besides having potentially

expansive psychological dimensions, placebo acupuncture involves highly focused

directed attention that is enveloped by unique kinds of apprehension,

anxiety and trust and autonomic arousal, more akin to what happens in a

multi-sensory healing ritual than the more medical behavior of simply taking a

pill” (6)

From Placebos

without Deception: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: (7)

“Patients were randomized to either open-label placebo

pills presented as “placebo pills made of an inert substance, like sugar pills,

that have been shown in clinical studies to produce significant improvement in

IBS symptoms through mind-body self-healing processes” or

no-treatment controls with the same quality of interaction with providers.

Open-label placebo produced significantly higher mean global improvement scores

at both 11-day midpoint and at 21-day endpoint…. Placebos administered without deception may be an effective

treatment for IBS.”

[Compilers’

observation: Patients were told that the pills do work, and

that clinical studies had shown this. They were even told how they work

– "through mind-body self-healing process". This is for most people

an explanation at least as comprehensible and rational as being told that they

work by blocking the potassium channel or selectively inhibiting serotonin

re-uptake.]

F Fabrizio Benedetti, M.D. - Professor of Physiology and Neuroscience, University of Turin - PiPs*

“Any medical treatment is surrounded

by a psychosocial context that affects the therapeutic outcome. If we want to

study this psychosocial context, we need to eliminate the specific action of a

therapy and to simulate a context that is similar in all respects to that of a

real treatment. To do this, a sham treatment (the placebo) is given, but the

patient believes it is effective and expects a clinical improvement. The

placebo effect, or response, is the outcome after the sham treatment.

Therefore, it is important to emphasize that the study of the placebo effect is

the study of the psychosocial context around the patient.

The placebo effect is a

psychobiological phenomenon that can be attributable to different mechanisms,

including expectation of clinical improvement and Pavlovian conditioning. Thus,

we have to look for different mechanisms in different conditions, because there

is not a single placebo effect but many. So far, most of the neurobiological

mechanisms underlying this complex phenomenon have been studied in the field of

pain and analgesia, although recent investigations have successfully been

performed in the immune system, motor disorders, and depression. Overall, the

placebo effect appears to be a very good model to understand how a complex

mental activity, such as expectancy, interacts with different neuronal

systems.” (8)

Nocebo:

(From Guardian UK article)

… Until recently, we knew very little about how

the nocebo effect works. Now, however, a number of scientists are beginning to

make headway. A study in February led by Oxford's Professor Irene Tracey showed

that when volunteers feel nocebo pain, corresponding brain activity is

detectable in an MRI scanner. This shows that, at the neurological level at

least, these volunteers really are responding to actual, non-imaginary, pain.

Fabrizio Benedetti and his colleagues have managed to determine one of the

neurochemicals responsible for converting the expectation of pain into this

genuine pain perception. The chemical is called cholecystokinin and

carries messages between nerve cells. When drugs are used to block

cholecystokinin from functioning, patients feel no nocebo pain, despite being

just as anxious.

The findings of Benedetti and Tracey not only

offer the first glimpses into the neurology underlying the nocebo effect, but

also have very real medical implications. Benedetti's work on blocking

cholecystokinin could pave the way for techniques that remove nocebo outcomes

from medical procedures, as well as hinting at more general treatments for both

pain and anxiety. The findings of Tracey's team carry startling implications

for the way we practise modern medicine. By monitoring pain levels in

volunteers who had been given a strong opioid painkiller, they found that

telling a volunteer the drug had now worn off was enough for a person's pain to

return to the levels it was at before they were given the drug. This indicates

that a patient's negative expectations have the power to undermine the

effectiveness of a treatment, and suggests that doctors would do well to treat

the beliefs of their patients, not just their physical symptoms…. (9)

F Tor D. Wager

(Professor of psychology at the University of Colorado)

Wager’s specialty is neuroscience and brain imaging,

but his passion is the placebo effect – a phenomenon being studied by

researchers in many corners of science. He has written roughly a dozen scientific papers on placebo effects,

including a 2007 study linking pain-related effects to parts of the brain that

process opium or heroin (which may help explain why many placebos are

temporary) – and concluded that “Placebo-induced

expectancies of pain relief have been shown to decrease pain in a manner

reversible by opioid antagonists, but little is known about the central brain

mechanisms of opioid release during placebo treatment.”

For

Wager, the issue of placebo effects entails a deep question, tied to his

childhood religion (Christian Science) and the way he sees the world. Through

his various experiments he discovered that the brain creates the desired chemicals

when a placebo is introduced. In one experiment Wager placed a heating pad on

the test subject’s arm. This caused the subject discomfort, which Wager stated

would go away when he put a pain relief ointment on the subject’s skin. Rather

than doing so, Wager used the equivalent of Vaseline. The moment the placebo

was introduced, the subject was given a brain scan. Wager discovered that the

temporal lobes became excited and then they activated the limbic system, which

is the main producer of opioids…. Wager concluded that the brain can be tricked

into creating chemicals that it wouldn’t normally produce. Wager has done

further experiments with morphine that have allowed patients to be slowly

weaned off a morphine addiction by giving them the basic equivalent of a sugar

pill. “What is the placebo

effect? Well, it’s not some weird magical thing that just kind of happened out

of the blue. I think it’s connected to systems that generate emotional

responses. It’s a window into ways in which psychological factors can affect

brain and body factors that are related to health.” (Source - NY Times)

F Dan Moerman, Phd. – Anthropologist, Department of Behavioral Sciences, University of

Michigan-Dearborn, USA

- PiPs*

(Key

points: Paper entitled “Deconstructing the Placebo Effect and Finding the

Meaning Response” co-published by Daniel E. Moerman, PhD, and Wayne B. Jonas, MD (10)

·

The one thing of which we can be absolutely certain is that placebos do

not cause placebo effects. Placebos are inert and don’t cause anything.

·

Ironically, although

placebos clearly cannot do anything themselves, their meaning can.

·

We define the meaning

response as the physiologic or psychological effects of meaning

in the origins or treatment of illness; meaning responses elicited after the

use of inert or sham treatment can be called the “placebo effect” when they are

desirable and the “nocebo effect” when they are undesirable.

·

Insofar as medicine is meaningful, it can affect patients, and it can

affect the outcome of treatment. Most elements of medicine are meaningful,

even if practitioners do not intend them to be so. The physician’s costume (the

white coat with stethoscope hanging out of the pocket), manner (enthusiastic or

not), style (therapeutic or experimental), and language, are all meaningful

and can be shown to affect the outcome; indeed, we argue that both diagnosis

and prognosis can be important forms of treatment.

·

Meaning Can Have Substantial Physiologic Action: Placebo analgesia can

elicit the production of endogenous opiates. Analgesia elicited with an

injection of saline solution can be reversed with the opiate antagonist

naloxone and enhanced with the opiate agonist proglumide. Likewise, acupuncture

analgesia can be reversed with naloxone in animals and people.

To

say that a treatment such as acupuncture “isn’t better than placebo” does not

mean that it does nothing.

·

Meaning and Surgery: The classic example of the meaningful effects of surgery

comes from two studies of ligation of the bilateral internal mammary arteries

as a treatment for angina. Patients receiving sham surgery did as well – with

80% of patients substantially improving – as those receiving the active

procedure in the trials or in general practice. Although the studies were

small, the procedure was no longer performed after these reports were

published. Of note, these effectiveness rates (and those reported by the

proponents of the procedure at the time) are much the same as those achieved by

contemporary treatments such as coronary artery bypass or beta-blockers.

·

Surgery is particularly meaningful: Surgeons are among the elite of

medical practitioners; the shedding of blood is inevitably meaningful in and of

itself. In addition, surgical procedures usually have compelling rational

explanations, which drug treatments often do not. The logic of arthroscopic

surgery (“we will clean up a messy joint”) is much more sensible and

understandable (and even effective, especially for people in a culture rich in

machines and tools, than is the logic of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(which “inhibit the production of prostaglandins which are involved in the

inflammatory process,” something no one would ever tell a patient). Surgery

clearly induces a profound meaning response in modern medical practice.

·

MEANING, CULTURE, AND MEDICINE: Anthropologists

understand cultures as complex webs of meaning, rich skeins of connected

understandings, metaphors, and signs. Insofar as 1) meaning has biological

consequence and 2) meanings vary across cultures, we can anticipate that

biology will differ in different places, not because of genetics but because of

these entangled ideas; we can anticipate what Margaret Lock has called “local

biologies”; Lock has shown dramatic cross-cultural variation in the existence

and experience of “menopause”. Moreover, Phillips has shown that “Chinese

Americans, but not whites, die significantly earlier than normal (1.3 to 4.9

yr) if they have a combination of disease and birth year which Chinese

astrology and medicine consider ill fated”. Among Chinese Americans whose

deaths were attributed to lymphatic cancer (n= 3041), those who were

born in “Earth years” – and consequently were deemed by Chinese medical theory

to be especially susceptible to diseases involving lumps, nodules, or tumors –

had an average age at death of 59.7 years. In contrast, among those born in

other years, age at death of Chinese Americans with lymphatic cancer was 63.6

years – nearly 4 years longer. Similar differences were also found for various

other serious diseases. No such differences were evident in a large series of

“whites” that died of similar causes in the same period. The intensity of the

effect was shown to be correlated with “the strength of commitment to

traditional Chinese culture.” These differences in longevity (up to 6% or 7%

difference in length of life!) are not due to having Chinese genes but to

having Chinese ideas, to knowing the world in Chinese ways. The effects of

meaning on health and disease are not restricted to placebos or brand names but

permeate life.

·

CONCLUSIONS:

Practitioners

can benefit clinically by conceptualizing this issue in terms of the meaning

response rather than the placebo effect. Placebos are inert. You can’t do

anything about them. For human beings, meaning is everything that

placebos are not, richly alive and powerful. However, we know little of this

power, although all clinicians have experienced it.

One

reason we are so ignorant is that – by focusing on placebos – we constantly

have to address the moral and ethical issues of prescribing inert treatments,

of lying, and the like. It seems possible to evade the entire issue by simply

avoiding placebos. One cannot, however, avoid meaning while engaging human

beings. Even the most distant objects – the planet Venus, the stars in the

constellation Orion – are meaningful to us, as well as to others.

Yet,

a huge puzzle remains: Obviously the meaning response is of great value

to the sick and the lame. For example, eliciting the meaning response requires

remarkably little effort (“You will be fine, Mr. Smith”). So why doesn’t this

happen all the time? And why can’t you do it to yourself? Psychologist Nicholas

Humphrey has suggested that this conundrum may have evolutionary roots: Healing

has its benefits but also its costs. (For example, relieving pain may encourage

premature activity, which could exacerbate the injury. Moreover, immune

activity is metabolically very demanding on an injured system.) Perhaps only

when a friend, relative, or healer indicates some level of social support (for

example, by performing a ritual) is the individual’s internal economy able to

act. Moreover, as we have clarified, routinized, and rationalized our medicine,

thereby relying on the salicylates and forgetting about the more meaningful

birches, willows, and wintergreen from which they came – in essence, stripping

away Plato’s “charms” – we have impoverished the meaning of our medicine to a

degree that it simply doesn’t work as well as it might any more. Interesting

ideas such as this are impossible to entertain when we discuss placebos; they

spring readily to mind when we talk about meaning. (10)

F Nicholas

Humphrey - evolutionary psychologist; Professor Emeritus, London School of Economics &

Political Science - PiPs*

“Wherever a

capacity for self-cure exists as a latent possibility in principle,

placebos will be found to activate this capacity in practice. It’s true that

the effects may not always be consistent or entirely successful. But they certainly

occur with sufficient regularity and on a sufficient scale to ensure that they

can and do make a highly significant contribution to human health….

Evolutionary

theory suggests that the human capacity to respond to placebos must in the past

have had a major impact on people’s chances of survival and reproduction (as

indeed it does today), which means that it must have been subject to strong

pressure from natural selection. This capacity apparently involves dedicated

pathways linking the brain and the healing systems, which certainly look is if

they have been designed to play this very role…

The human

capacity for responding to placebos is in fact not necessarily adaptive in its

own right (indeed it can sometimes even be maladaptive). Instead, this capacity

is an emergent property of something else that is genuinely adaptive:

namely, a specially designed procedure for ‘economic resource management’ that

is, I believe, one of the key features of the ‘natural health-care service’

which has evolved in ourselves and other animals to help us deal throughout our

lives with repeated bouts of sickness, injury, and other threats to our

well-being…

When the

sickness is self-generated, cure can be achieved simply by switching off whatever

internal process is responsible for generating the symptoms in the first place;

with pain, for example, you may well be able to achieve relief simply by

sending a barrage of nerve signals down your own spinal cord or by releasing a

small amount of endogenous opiate molecules. Similarly, with depression, you

may be able to lift your mood simply by producing some extra seritonin.

However, it

may be a very different story when the sickness involves genuine pathology and

the cure requires extensive repair work or a drawn-out battle against foreign

invaders – as with healing a wound or fighting an infection or cancer…

People’s bodies and minds have a considerable capacity for

curing themselves. Sometimes this capacity for self-cure is not expressed spontaneously,

but can be triggered by the influence of a third party. In such cases,

self-cure is being inhibited until the third-party influence releases it. When

self-cure is inhibited there must be good reason for this under the existing

circumstances; and when inhibition is lifted there must be good reason for this

under the new circumstances. The good reason for inhibiting self-cure must be

that the subject is likely to be better off, for the time being, not being

cured. Either there must be benefits to remaining sick, or there must be costs

to the process of self-cure. The good reason for lifting the inhibition must be

that the subject is now likely to be better off if self-cure goes ahead. Either

the benefits of remaining sick must now be less, or the costs of the process of

self-cure must now be less…

Many of those

conditions from which people seek relief are not in fact defects in themselves

but rather self-generated defenses against another more real defect or

threat. Pain is the most obvious example. Pain is not itself a case of bodily

damage or malfunction – it is an adaptive response to it. The main function of

your feeling pain is to deter you from incurring further injury, and to

encourage you to hole up and rest. Unpleasant as it may be, pain is nonetheless

generally a good thing – not so much a problem as a part of the

solution.

It’s a

similar story with many other nasty symptoms. For example, fever associated

with infection is a way of helping you to fight off the invading bacteria or

viruses. Vomiting serves to rid your body of toxins. And the same for certain

psychological symptoms too. Phobias serve to limit your exposure to potential

dangers. Depression can help bring about a change in your life style. Crying

and tears signal your need for love or care. And so on. Now, just to the extent

that these evolved defenses are indeed defenses against something worse,

it stands to reason that there will be benefits to keeping them in place

and costs to premature cure.

If you don’t

feel pain you’re much more likely to exacerbate an injury; if you have your

bout of influenza controlled by aspirin you may take considerably longer to

recover; if you take Prozac to avoid facing social reality you may end up

repeating the same mistakes, and so on. The moral is: sometimes it really is

good to keep on feeling bad. On the other hand ….

What placebo

treatments do, is to precisely give people reason to hope, albeit that the

reason may in fact be specious. No matter, it works!… Your evolved health-care

management system may sometimes make egregious errors in the allocation

of resources – errors which you can only undo by overriding the system

with a placebo response based on invalid hope…” (11)

F Howard L. Fields, MD, PhD - Professor of

Neurology and Physiology, UCSF - PiPs*

Professor Fields is also

Director of Human Clinical Research, Gallo

Center and the Wheeler

Center for the Neurobiology of Addiction, and he notes how

our brains are powerfully affected by others’ words, body language and tone of

voice – to the extent of reducing the effect of drugs (and reduced need for

them), and – in the case of placebos – when subjects are advised of

‘side-effects’, they tend to get them. He emphasizes that our lives are all

unique (even in the case of identical twins) because of our having learned from

ongoing, personally unique experiences

– including formal and informal education, books, observation and social

environment – all of which give each of us a world-view different from any

others, and because of that, different things affect each person differently.

The

following comments were drawn from Setting

the Stage for Pain - Allegorical Tales from Neuroscience

by Professor Fields: (12)

“Since our subjective experience of self, body, and world is an emergent

property of dynamic networks of coordinated neural activity, the brain must

contain representations of the body, the self (mind), and the external world.

These representations give rise to the ongoing subjective experience of the

individual. Representations are a neural (physical) embodiment of meaning that

is often understood in the context of intention. Intention assumes goals; goals